In a world increasingly shaped by globalization and advanced technology, a new reality is emerging: the waning power of nation-states and the steady rise of corporate-ruled entities. Once the bedrock of sovereignty, governments now find themselves competing—and often cooperating—with megacorporations and technocratic elites for influence. As some corporations surpass national GDPs and tech giants control essential digital infrastructure, the lines between public governance and private authority begin to blur. This shift signals what many theorists call “The End of Nations”—where the future may be ruled less by democratically elected governments and more by powerful, technology-driven corporate structures.

1. The Decline of National Power

Historically, nations maintained power by controlling physical borders, distributing resources (such as welfare benefits or infrastructure), and providing the security and stability that citizens demanded. However, the digital age redefines these pillars:

- Global Markets and Supply Chains: Companies operate seamlessly across borders, relying on transnational networks for production and logistics. Governments, on the other hand, have limited leverage to regulate or tax corporations effectively when major corporate entities can shift operations or finances to more favorable jurisdictions.

- Eroding Regulatory Reach: In the digital domain, national regulations struggle to keep pace with technological innovations. Cryptocurrencies, decentralized platforms, and global social media networks often slip beyond the grasp of traditional bureaucracies.

- Diminishing Tax Revenues: As corporations optimize tax strategies by exploiting legal loopholes, governments face shrinking budgets—undermining their ability to sustain the traditional social contract that underpins their legitimacy.

2. The Rise of Corporate and Technocratic Empires

As governmental influence recedes, corporations and technocratic elites have stepped into the vacuum:

- Technological Infrastructure: Control over data processing, cloud services, artificial intelligence, and social media platforms grants these entities unprecedented power. They not only shape public opinion but also provide essential digital services, like communication platforms and online marketplaces, that citizens rely on daily.

- Private Governance Models: Some forward-looking corporations are establishing “company towns,” fully controlled campuses, or digital platforms with their own codes of conduct. Residents and users effectively become governed by corporate policies rather than public laws when interacting in these spaces.

- Microstates and Enclaves: Tech-driven startups and high-wealth individuals envision creating their own enclaves—physical or virtual—where they exercise autonomous governance. These enclaves promise efficiency and innovation, even as they raise concerns about transparency and accountability.

3. Shifting Definitions of Citizenship and Rights

In a landscape dominated by corporate rule, traditional citizenship can lose its meaning. Instead, people may become:

- “Customers” Rather Than Citizens: Instead of enjoying constitutional rights guaranteed by a state, individuals often find themselves subject to terms-of-service agreements crafted by private corporations. If a platform bans an individual, that person effectively loses access to digital services crucial for modern life.

- Data Commodities: As we generate data through smartphones, wearables, and social media, we unwittingly feed corporate databases that both serve and surveil us. This data is then monetized and used to enhance corporate power—sometimes without meaningful public oversight.

- Subjects to Corporate Law: Conflicts within these enclaves or platforms may be settled not in public courts, but through private arbitration or internal corporate tribunals. This raises the critical question: who guarantees fairness or protects individual rights when the corporation is the de facto “judge”?

4. Neo-Feudalism in the Digital Age

Parallel to historical feudalism, where lords provided security and land in exchange for service, we might see a modern twist:

- Economic Dependence: Corporate enclaves offer high-paying jobs, quality healthcare, private schooling, and gated security. In exchange, residents pledge loyalty, often with limited ability to challenge corporate authority.

- Hierarchical Power Structures: The “tech lords” or corporate elites may hold unparalleled economic, informational, and technological might. This power disparity can entrench social hierarchies, particularly when no strong external force—like a traditional government—enforces checks and balances.

- Moral Dilemmas: Individuals receive security and convenience, yet they must surrender privacy, freedom of speech, or ownership of personal data. As with feudal times, leaving the “land” (the platform or enclave) might mean losing one’s livelihood or access to vital resources.

5. Philosophical and Ethical Considerations

- Legitimacy and Governance

Where does legitimate authority come from if not from a democratic mandate? Some corporate rulers might claim it comes from efficiency, innovation, or the ability to provide valuable services. Others argue that authority lacking democratic input risks devolving into despotism—no matter how streamlined or profitable the system may be. - Social Contract Redux

Philosophers from Thomas Hobbes to Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed that societies function best when individuals consent (implicitly or explicitly) to governance that ensures collective well-being. In the new corporate order, “consent” could be replaced by user agreements—rarely read and almost never negotiated by individuals, raising moral questions about real autonomy and choice. - Impact on Democratic Ideals

If corporations or technocrats allocate essential resources, they decide who benefits—and on what terms. Without democratic oversight, will these new powerbrokers prioritize profit at the expense of societal welfare? Can there be genuine public accountability if leaders are selected by corporate boards rather than elections? - Potential for Innovation

On the flip side, corporate and technocratic structures can be highly efficient, investing heavily in research, automation, and infrastructure. When free from political gridlock, they might drive rapid technological progress. Critics point out, however, that rapid innovation without oversight can exacerbate inequality and social disruption.

6. Strategic Implications for Individuals and Institutions

- Aligning with Corporate Power

- Governments seeking stability may partner with corporations, leveraging private investment for public initiatives. This can offer short-term benefits at the potential cost of long-term autonomy.

- Citizens, meanwhile, might feel compelled to “pledge” to certain platforms or megacorporations for employment and services—a modern vassalage of sorts.

- Creating Tech-Backed Microstates

- Entrepreneurial visionaries aim to build private city-states or floating enclaves, funded by blockchain-backed cryptocurrencies. Their argument: these enclaves can become catalysts for social experiments free from red tape.

- Detractors fear that such microstates could become havens of elitism, lacking basic protections for vulnerable populations.

- Decentralizing Governance

- Blockchain and decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) may offer an alternative to top-down corporate rule. By distributing decision-making across a network, DAOs strive for transparency and communal involvement.

- However, even DAOs risk “digital oligarchy” if a small group of savvy participants accumulates disproportionate voting power.

7. Looking Ahead: A Fork in the Road?

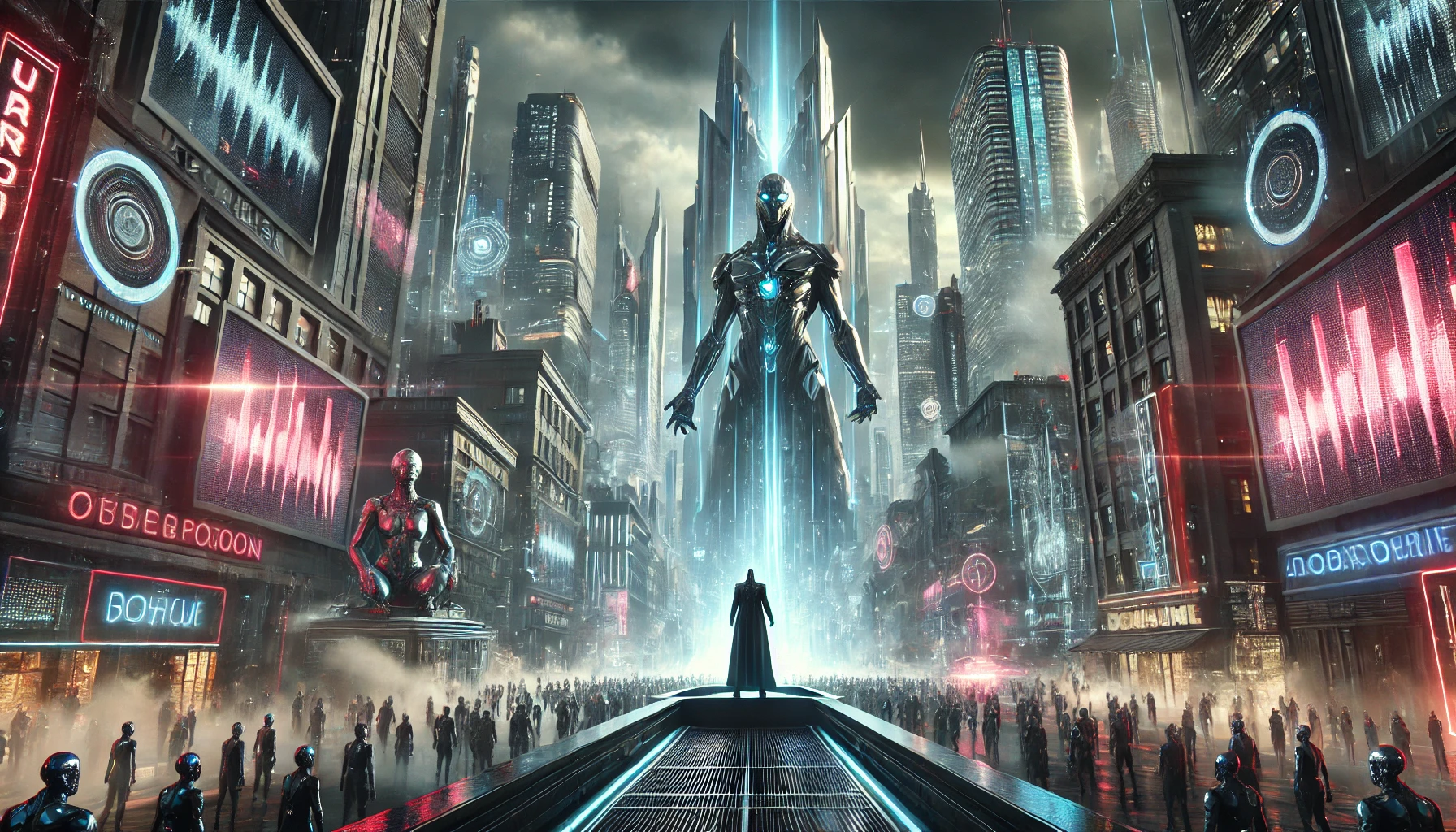

As the locus of power shifts toward corporate and technocratic entities, humanity faces a defining dilemma: Will this future lead to a dystopia where private elites dominate unaccountably, or can it spark new forms of socially responsible innovation and self-governance?

- Scenario A—Managed Dystopia: Corporate enclaves become digital fortresses, carefully selecting who gets in, using data to surveil and control residents. Freedoms outside the enclaves may shrink, while a privileged minority enjoys unparalleled comfort and security inside.

- Scenario B—Emergent Utopia: Freed from bureaucratic inertia, private and technocratic leaders innovate swiftly, solving global challenges such as climate change or pandemics. Competition among enclaves could stimulate better governance practices, offering citizens multiple options and fostering a new brand of accountability.

- Scenario C—Hybrid Models: Nation-states collaborate with corporations to form mixed governance structures, balancing private innovation with public oversight. Civil society could evolve to advocate for tech ethics, ensuring that data-driven systems respect human rights.

Which scenario becomes reality depends on both policymakers and everyday individuals. If we relinquish critical decisions to corporate boards without vigilance, we may end up living by contracts we never consciously negotiated. Conversely, if we engage actively—demanding transparency, fair governance, and ethical technology—there is still room to shape a balanced future that harnesses innovation while upholding the dignity of every person.

Conclusion

“The End of Nations” does not necessarily mean the total dissolution of the state, but it suggests a profound transformation in how power is wielded and distributed. The rise of corporate and technocratic empires forces us to rethink foundational questions about sovereignty, human rights, and the social contract. As these private entities and digital platforms increasingly stand in for public institutions, society must grapple with whether this brave new order can preserve or enhance our shared values—or if it will leave us divided between those inside the walls of corporate enclaves and those outside, struggling to have a say in how they’re governed.